Beijing's Divine Music Administration

In Beijing there is the Temple of Heaven, a 273 hectare Imperial Sacrificial Altar complex built in 1420. The capital city of China for over three thousand years, Beijing was the home to the Chinese Emperor and Royal court. The Temple of Heaven as UNESCO says, “stands at the heart of Chinese cosmogony, and also the special role played by the emperors within that relationship.” Inside the Temple of Heaven there is an area called the Divine Music Administration. Formerly known as Temple of Divine Music, it was a school that taught zhonghe shaoyue -- or simply yayue, known in English as mourning and accession ceremonial music. The institution served to codify the sounds of Chinese Music and train musicians to perform in imperial Chinese rituals. Musicians and other ceremonial officials performed for the dignitaries including the “emperor at the imperial courts and took part in the most important national ceremony of Chinese dynasties that happened in winter at 3 am,” according to The State Council.

It was a humid day in July 2017 with my mans during our three-week trip that summer. We came upon this museum of Chinese music while lost in the Temple of Heaven. Alone in this block of the otherwise populous attraction, we explored its artwork, instruments and historical fact placards for hours.

The institution of the Divine Music Administration disbanded upon the collapse of the Qing Empire in 1912. It reemerged when the Temple of Heaven complex was opened as a cultural attraction in the late 1980s and became a UNESCO heritage site in 1998. It now serves as a museum and centre for the study of ritual Chinese music and imperial performance art).

Inside the main hall of the Divine Music Administration are displays of the traditional instruments and massive murals depicting Imperial musicians and ceremonies. On a plaque in this room, yayue is described as;

“[A] unique form of oriental music and dance only used by the imperial court. It combined ritual, music, song and dance into one … A mystical and wonderful ambience was thus created in which man and heaven dialogued, representing the highest ideal that man is an integral part of nature. … Here, a tour of Divine music will usher visitors … to listen to the sound of heaven as heard in remote ancient times.”

This style is authentic to Northeastern China and prominently features the recapitulation of traditional Chinese philosophy, poetry, and other musical and artistic themes (Rees 1998, 140). Western listeners may recognize some of the sounds of Ming and Qing China adapted into films like Hero from 2002 and Once Upon a Time in China from 1991. Official ceremonies taking place in Beijing were composed and performed to demonstrate “traditional” Chinese national identity for visitors at the Imperial court (Lawson 2011, 10). Historic pieces from the Ming and Qing dynasties are performed today at the Divine Music Administration with respective influences from thousands of years of Chinese musical tradition, technique, and history.

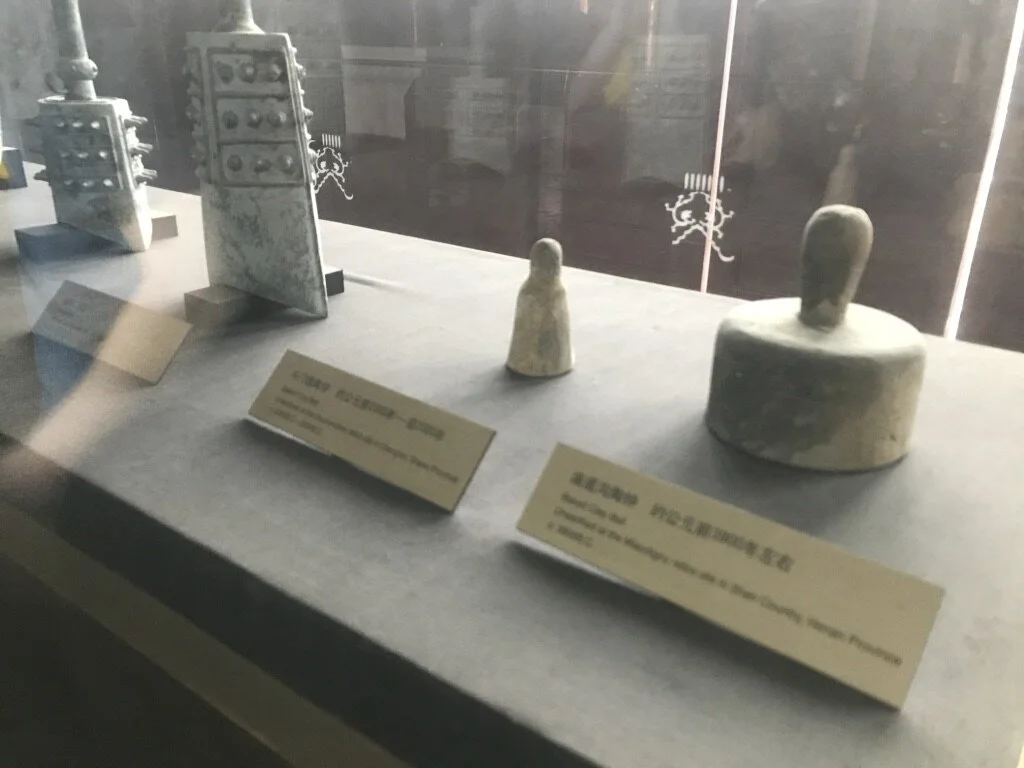

Ancient Chinese instruments included in the Divine Music Administration collection are the gu qin (part of the zither family category, greatly varying in size and age); zheng, chun, and duo -- various copper, gong- or bell-like percussive instruments; xiao (wooden, vertical flutes); jiangu (a leather drum); and chongdu, zhu, ya and yu (shaped and painted to resemble a tiger) are wooden percussions. These belong to the primary classifications used in East Asian music of zithers, chordophones, idiophones, aerophones and membranophones. Percussive instruments were multipurpose and usually signified the start or stop of a zhonghu shaoyue piece. Copper and bell instruments accompany the drums and are mainly used in military, royal and other official activities.

“Shi Chao Yuan” is an undated example of yayue music and dance that may have been played for Ming and Qing emperors at formal settings. Unattributed to a composer the piece is part of the written music collection of the Xi’an Buddhist Classical Music Ensemble, according to NPR’s 2009 recording of the same Xi'an Buddhist Classical Music Ensemble performing with the Chang'an Women's Classical Music Ensemble. I listened to the 12-minute piece which features variants of copper and brass bells, wooden percussions, Chinese flutes (at this time all blanketed under the name xian), zithers, and prominently the erhu, a two-stringed bowed instrument. Besides the other two pieces included in the NPR recordings, “Shi Chao Yuan” stood out as featuring bells, wooden xian, and guqin zithers.

The changing movements in “Shi Chao Yuan” would accompany dance and ceremonial rituals by showing different colours in a single repertoire and ensemble for a grandiose effect. It represents ceremony and ritual in its composition, meaning and performance that demonstrates the historical way of doing so, traditional harmonic motifs, costume and ensemble arrangement. The repetition in the percussive parts and movements from beginning and at the end signifies an opening and close of a ceremony, or prelude and exit for a dance.

The piece varies in textures and form, with changes occurring every one to two minutes, noticeably with different instrumental section features. It is exciting to hear the instruments come to life: The first minute of “Shi Chao Yuan” includes metallic bells, pitched pentatonically in an E major scale playing over the wooden percussive tiger shaped blocks. It is keeping the strong pulses in a clear beat in an additive meter or polymeter/polyrhythm. The metallic timbre produces reverberating whirrs and clashes like cymbals or pots and demands attention with about three to eight different instruments, creating a varying texture of an otherwise steady group of polyrhythms. Halfway through the patterns, a low, rolling drum enters, crescendos for one measure, and repeats until the end of the section while the other percussions fall piano and then collectively hit the final downbeat beat in fortissimo. Accents are heavy on every other beat and there are flourishes with the drums.

A prominent display inside the modern iteration of the Divine Music Administration is titled “China’s study of the tonal system holds the lead in the world.” This tuning system was developed “by Chinese scientist Zhu Zaiyu in 1581, while in Europe, it was only in 1600 Stephen, a Netherlandish scientist put an interpretation on this issue mathematically,” it reads on a plaque at the Divine Music Administration. The system uses a mathematical formula to determine the relativity of notes to each other creating a functional twelve pitch system. A chromatic 12 tone scale is only harmonically viable by tuning the notes using a system where each pitch is slightly out of tune in relation to the harmonic series. In Chinese ritual music the focus is on melody and rhythm, which are simple and rooted in traditional melodic phrasing. There is little improvisation due to the formality and sacred meaning of the music.

The Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties of China spanned across the same time period as the Renaissance, Baroque, Romantic and Classical eras in European music. European historiography is remembered as a flow of innovative movements, as in Renaissance and Reformation. In Asia, religion and state were deeply intertwined while in Europe the state and church were separating. Chinese history is remembered as a flow of imperial dynasties and secular movements are largely absent in traditional histories. The concept of the divine right of kings was being challenged in the european communities which were experiencing a reformation in the church whereas in China the emperors were still firmly connected to the gods, divinity, and heaven.

The purpose of the Divine Music Administration was to codify sounds and musical practices including dances and other ceremonial rituals. It fulfills the truest statement of rituality in Chinese music as a heritage site which preserves knowledge in exhibits of cultural artifacts and music for native and non-Chinese audiences. The Divine Music Administration serves to perform music and rituals from the Ming and Qing dynasties in Beijing just as they might have been performed for Chinese emperors, reaffirming their connection to Heaven.

sources:

2017. Divine Music Administration, Temple of Heaven, Beijing, China. Tiantan Park. http://en.tiantanpark.com/default.asp.

“Music from the Temple of Heaven.” 2014. The State Council, The People's Republic Of China. Gov.cn. October 17. http://english.gov.cn/news/video/2014/10/17/content_281474998140895.htm.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 1998. “Temple of Heaven: an Imperial Sacrificial Altar in Beijing.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/881.

Zhu, Yu, orchestrator. "Si Chao Yuan (Formal Court Music)." Xi'an Buddhist Classical Music Ensemble and the Chang'an Women's Classical Music Ensemble. NPR. March 10, 2009. Accessed November 22, 2017. https://www.npr.org/2009/03/10/101626136/keeping-chinas-ancient-music-alive.

last updated on March 18, 2020